Each spring half term I go camping with my family and we visit a different British Isle. Its a week when I meet young conservationists out in the field – putting the hours in protecting tern colonies, showing visitors nesting peregrines, doing vegetation transects and the many other time-consuming seasonal tasks that conserving our nature entails.

I imagine how wonderful it must be to be young again with the opportunity to engage with nature daily over a season and to have the space to think, read and contemplate on life and futures. Through my job as a conservation MSc Course Director I am aware that conservation is changing – established ideas are being challenged and new visions are being formulated. I have put together a selection of books which are helping me think about conservation and which I recommend to conservationists young or old looking for a thought-provoking summer read.

I am sure there are other great forward-looking conservation reads out there and I’d love to hear your suggestions and your reactions to the five I have selected.

My first recommendation is not a conservation book. It is Sapiens,Yuval Noah Harari‘s brilliant and readable history of our species. He starts by reminding us that we were once one of six homo species that existed into the not too distance past, but quickly moves on to the cognitive revolution – the step change in how our brains work that has set us apart from other life on Earth.

My first recommendation is not a conservation book. It is Sapiens,Yuval Noah Harari‘s brilliant and readable history of our species. He starts by reminding us that we were once one of six homo species that existed into the not too distance past, but quickly moves on to the cognitive revolution – the step change in how our brains work that has set us apart from other life on Earth.

Harari explains how we sapiens developed the ability to imagine and communicate realities: to formulate collective myths and stories that enable coordinated action among large groups, across times and vast distances and between people who had never met each other. Pretty mind-blowing when you stop to think about it.

Harari marshals his sharp analysis of the cognitive revolution to provide insightful and revealing accounts of constructs such as money, empire, power, commerce and trade, that have not only shaped sapien history and identity, but also our way of knowing and acting in the world. With these conceptual resources he questions ideas of progress, pointing out that hunter-gathers likely lived happy and fulfilled lives and our stories led to lives of drudgery and enslavement for peoples during the agricultural and industrial revolutions.

A read of Sapiens is like downloading software for the conservationists mind. It provides the conceptual resources to think about deep questions in conservation: how has our species come to have such an impact on the planet? why do so many people seem disconnected from nature? and how has conservation come to be a cultural force and can it remain so?

Sapiens is as near as you’ll get to a theory of humankind.

My second forward-looking read is another history. In The Invention of Nature. Alexander von Humboldt’s New World, Andrea Wulf, reminds us that the natural sciences had a Shakespeare and his name was Alexander von Humbolt. In the 19th century his fame was such that the centenary of his birth in 1869 was marked with parades and celebrations in cities across the US. Subsequently science and society forgot him, perhaps because he didn’t formulate a major theory or perhaps because he was German and Nazism made celebrating German scientific brilliance uncool.

My second forward-looking read is another history. In The Invention of Nature. Alexander von Humboldt’s New World, Andrea Wulf, reminds us that the natural sciences had a Shakespeare and his name was Alexander von Humbolt. In the 19th century his fame was such that the centenary of his birth in 1869 was marked with parades and celebrations in cities across the US. Subsequently science and society forgot him, perhaps because he didn’t formulate a major theory or perhaps because he was German and Nazism made celebrating German scientific brilliance uncool.

Whatever the reason, Wulf superbly explains the genius of von Humbolt’s massive influence on human understandings of the natural world and the emergence of new political orders in the Americas. The first part of the book is a biography of this truly amazing man and his travels in Europe and in particular present day Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, Columbia and Mexico. Humbolt was arguably the greatest polymaths ever, not only intellectually but also physically (if thats possible!). He had an extraordinary photographic memory, amazing powers of lateral thinking, superb sensory ability, singular drive, stamina and ambition all combined with a huge curiosity and thirst for knowledge. This guy climbed Chimborazo in 18th century clothes and while suffering exposure and altitude sickness continued to systematically take measurements with his his heavy instruments and at 22,000 ft sat down, surveyed the vista and consolidated ground breaking ideas on altitudinal zonation!

“Humbolt was one of those wonders of the world, like Aristotle, like Julius Caesar ….who appear from time to time as if to show us the possibilities of the human mind, the force and range of the faculties – a universal man”. – Raplh Waldo Emerson,1869

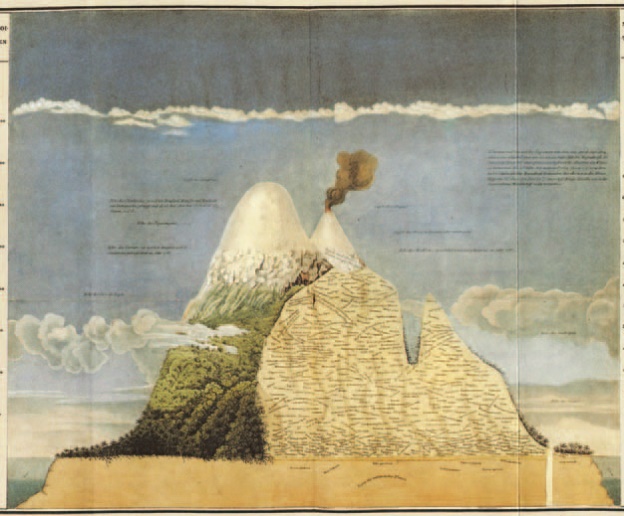

What Wulf does brilliantly is point out just how progressive von Humbolt was in both his ideas and  the way he communicated them. He invented isobars (where would weather forecasters be without them!) and his famous Naturgemaelde was the first ever info-graphic and is still one of the the best.

the way he communicated them. He invented isobars (where would weather forecasters be without them!) and his famous Naturgemaelde was the first ever info-graphic and is still one of the the best.

In the second part of the book she explores the influence of von Humbolt on political leaders of his time and the scientists and writers who laid laid the scientific and intellectual foundations of conservation. She describes his influence on Simon Bolivar, the revolutionary who helped free several South America states from Spanish rule, and on Thomas Jefferson, lead author of the American Declaration of Independence. Of particular relevance to conservationists is her analysis of the influence of Humbolt’s books on Charles Darwin and three ‘founding fathers’ of US conservation: Henry David Thoreau, George Perkins Marsh and John Muir.

Humbolt lived at a time when one gifted person could just about grasp the entirety of scientific knowledge. Subsequently science split into specialist disciplines and integrated thinking suffered as a result. Conservation science is moving towards interdisciplinarity in order to meet the challenges or effecting change in our complex world. Andrea Wulf reminds us that holistic science is nothing new and that in Humbolt conservation science can trace its origins to a true genius.

My third read is Emma Marris’ Rambunctious Garden: saving nature in a post-wild world. Everyone seems to be discussing rewilding and the number of articles on the topic is expanding every day. This is a great introductory read for those looking to understand that transformations in thinking that rewilding signifies.

My third read is Emma Marris’ Rambunctious Garden: saving nature in a post-wild world. Everyone seems to be discussing rewilding and the number of articles on the topic is expanding every day. This is a great introductory read for those looking to understand that transformations in thinking that rewilding signifies.

It is an optimistic conservation book where Marris argues that if conservationists let go of ideas that past natures were better, we can work with social and environmental change to create rich new natures and extend nature conservation beyond reserves.

Marris’ examples and arguments are strongly situated in US conservation thinking and, like many social scientists, she over states the influence of concepts of pristinity and wilderness in conservation policy and practice. None-the-less she pushes the reader to think about what is meant by concepts such as nature, wilderness, and conservation. She also questions taken-for-granted policy frames such as those relating to the undesirability of invasive and non-native species.

Throughout the book she blends case study examples and science to show how ecosystems have always been changing and continuing to do so whether we like it or not. This speaks to the issue of baselines which is a key pillar of the rewidling arguments: what era or type of nature should we conserve and restore to and who decides? If nature has always been dynamic and changing then why don’t we go with this reality and work to ‘steer’ or design ecosystems to produce richer future natures and natures that are accessible to all? Marris goes on to describe conservation approaches that are exploring this type of thinking, including assisted migration, rewilding, the creation or embracing of novel ecosystems.

By making explicit and unsettling taken-for-granted ways of thinking, Rambunctious Garden is not an easy read but it is one that prompts conservationists to ask if society and environment is undergoing change does conservation need to do likewise?

My forth book is truly forwarding-looking and a master piece of popular science writing. Beth Shaprio’s How to clone a Mammoth is a must read for anyone wanting to engage with up-and-coming ethical and strategic debates in conservation.

My forth book is truly forwarding-looking and a master piece of popular science writing. Beth Shaprio’s How to clone a Mammoth is a must read for anyone wanting to engage with up-and-coming ethical and strategic debates in conservation.

Shaprio is a leading figure in the field of ancient DNA, a field that interacts with the fast moving science of synthetic biology and scientists working to reassemble DNA sequences to resurrect lost species such as the mammoths. What she does brilliantly is explain the techniques and prospects of ‘de-extinction’ science, introduce the people and research groups involved, and explore the ethical implications of their research visions for conservation.

De-extinction can be thought of as the extreme edge of rewilding: a future where extinct species that played a role in the functioning of past ecosystems are recreated using genomic techniques. De-extinction is already part of European rewilding: herds of cattle the look and function like aurochs are being restored to several sites in Eastern Europe. The auroch went extinct in 1621 but its DNA lived on in domestic cattle breeds making de-extinction relatively straight-forward using genomic ‘guided’ back-breeding.

Shapiro’s focus is the work of the small cadre of scientists exploring he vision of bringing back species whose DNA exists only in remains e.g. frozen mammoth carcasses. She is a realists and clear in her view that such species can never be ‘dextincted’: what might be possible is inserting DNA sequences into a living species to create, for example an elephant with mammoth-like traits.

“Extinction is forever’ was a rallying cry of the late 20th century conservation movement and Shapiro examines both the risk of unsettling this widely accepted truism and what would count as de-extinction – does a mammoth-like elephant in a zoo count or should de-extinction be reserved for a herd of mammoth-like elephants roaming Zimov’s Pleistocene Park?

The ethical and other issues raised by de-extinction science are many and make for creative discussions. For instance: Is it right to apply such techniques to animals? What would the legal status of de-extincted species be and if it was at risk of extinction a second time would we be compelled to save it? Should we be spending resources on resurrection extinct species when there are many extant species in need of saving?

Whatever ones personal views on these questions, the de-extinction debate looks set to happen sooner rather than later and How to clone a mammoth is a fantastic primer to the science, prospects and issues of de-extinction.

I dithered over whether or not to include my fifth read. Richard Louv’s Nature Principle.Human restoration and the end of Nature-Deficit disorder is an example of American green evangelism: a sermon on how (re)finding nature enriches life and offers a cure for the ills of modern living such as stress, depression, loneliness and disenfranchisement. Neuv coined the term nature deficit-disorder to describe the impacts of a loss of connection with nature and through this brought into focus the health, learning and social benefits that living with nature brings, even if the nature concerned it just a picture in a hospital room or office

I dithered over whether or not to include my fifth read. Richard Louv’s Nature Principle.Human restoration and the end of Nature-Deficit disorder is an example of American green evangelism: a sermon on how (re)finding nature enriches life and offers a cure for the ills of modern living such as stress, depression, loneliness and disenfranchisement. Neuv coined the term nature deficit-disorder to describe the impacts of a loss of connection with nature and through this brought into focus the health, learning and social benefits that living with nature brings, even if the nature concerned it just a picture in a hospital room or office

“the natural world is not only a set of constraints but also the context within which we can realise our dreams” – Paul Shepherd

The early chapters, in particular, offer several nuggets of deep insight backed up by a decent account of current science, that will interest and inspire those of us seeking to connect conservation with broader social trends and policy. Nuev is particularly good at making the connections between health policy and well-being or in his words ‘sustainable happiness”

Much of what Nuev has to say will seem familiar and intuitively right to grounded conservationists. The value of the book is that it brings all the arguments and evidence together in one package.

The second part of the book is more a collection of tails of folks doing good work helping others to access Vitamin-N. The accounts are predominantly American, but I had little difficulty in thinking of comparable European examples going back decades.

In his last chapter, Neuv talks about the need to create a 3rd generation environmental narrative suited for the 21st century. I couldn’t agree more. First generation narratives of finite Earth and catastrophe and second generation narratives of natural capital and benefits have had major policy impact but they can also alienate people.

Together these five books contribute to a new conservation narrative based on restoring ecosystems and reconnecting people and economy across multiple scales and in diverse places and ways. It is narrative that reconnects the natural and social sciences and expresses new confidence and ambition.