Originally published in The Conversation on 21 April 2016

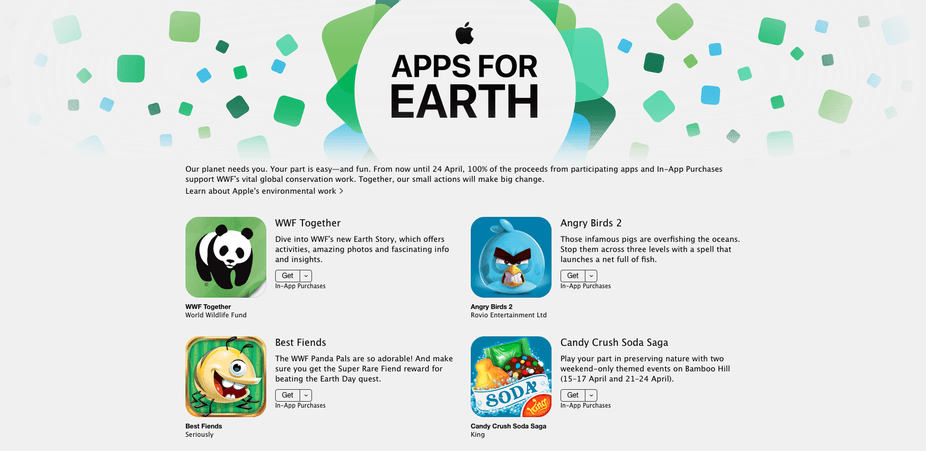

To mark Earth Day, Apple has launched Apps for Earth: a one week fundraiser for the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) involving 27 popular gaming and utility apps that have developed special paid-for content and an environmentally themed front page to the App store.

This partnership between Apple and WWF is symbolic of the rise of consumer environmentalism in our technological age – the idea that environmental concerns can be integrated into the production, purchase and use of consumer products and services.

The first Earth Day, held at the height of the US counterculture movement on April 22, 1970, expressed a new environmental consciousness that galvanised a rapid and high-level political response. An estimated 20m people attended demonstrations and rallies calling for an end to polluting industries and making the point that healthy environments and quality lifestyles are interlinked. It lead to many of the environmental laws and institutions that we nowadays take for granted.

Over the decades Earth Day has had a number of successful refreshes and now claims to be the largest secular observance in the world, involving more than a billion people every year. Maintaining and broadening engagement with the environmental movement is what it is all about.

Apps for Earth certainly has the potential to build support among Apple’s tech-savy, global, middle-class customer base, but the direct financial contribution to WWF maybe more modest: Apple’s partnership with the Aids charity (RED) has raised US$100m since 2006. While this is a significant sum for any NGO it equates to just 0.18% of Apple’s US$53.4 billion net income in 2015.

Carter Roberts, CEO of WWF-US, sees Apps for Earth as an example of the rich creativity and the big ideas with big impact that will enable it to succeed in its work. I am not so sure.

From a business sustainability perspective this is a conventional deal: all parties benefit in terms of growth, productivity and risk management. Apple gains WWF’s endorsement for its efforts to green its supply chainalong with a new “product” to offer its loyal customers, thereby enhancing and protecting its brand and motivating its environmentally-minded employees. WWF gains Apple and the tech media’s endorsement as the world leading conservation organisation and access to the tech-savy, middle class customer base of Apple’s App Store.

When it comes to saving the planet, big impact requires synergies between supporters and expertise. In a modern conservation organisation these imperatives are split between two professional “tribes” working in different departments and with different educations, career incentives and ways of working.

Simple messages, messy reality

At issue is the need for fundraisers and campaigners to communicate complex issues fast and in simple and appealing ways. This may not help build the deeper understandings required to generate support for the pragmatic solutions being developed by technical colleagues in programme departments, who engage with the messy and complex realities of the world over the long-term.

A case in the point concerns the massive investments in proposed new rail lines and roads that cut across protected natural habitats. Behind the scenes, conservation policy experts are generating frameworks, metrics, financial mechanisms along with the insider trust and influence needed to reduce environmental impacts, secure compensation where destruction of areas is unavoidable and identify win-wins where they exist. It’s a world of negotiation and compromise, of mitigation hierarchies and complex offset mechanisms, of shaping the future of the natural world as well as protecting the past.

This is modern conservation in practice, and it doesn’t translate easily into simple sound bites. It is increasingly at odds with the dominant fundraisier-campaigner narrative of “wonderful animals and landscapes which we will protect from the ills of the world for a small amount of your money, time and voice”.

Consumer environmentalism, such as Apps for Earth, aligns conservation with modern consumer culture. This offers fundraisers and campaigners the prospect of reaching new people and generating new funding streams, but it also carries the risk of ever more shallow public engagement and digital activism where masses of people get behind “solutions” that simply make themselves feel good.

For a decade or more those in conservation with the grounded, technical know-how have been working with tech giants such as Google to develop open access tools that that enable and empower better environmental management. One of the best examples is the Google Earth Engine that allows sophisticated analysis of geo-spatial information and the development of open-source alert and decision support tools such as Global Forest Watch. Such tools are extending the reach of environmentalism into everyday corporate and investment decision making.

Apple and Google have very different corporate ethos. Apple is founded on a belief in design and that simple things work, whereas Google believes in the power of data, is more collegiate and the engineers are king. Conservation fundraisers are attracted to Apple, while their more scientific colleagues are working with Google. Such alignments are understandable but they could also widen the gap between the popular and expert voices of environmentalism, creating a disjointed movement.

Earth Day needs to more than an opportunity for environmentalists to spread the word. It needs to be a day of coming together within the professional environmental movement. After all, the impact of half a million people marching down Fifth Avenue in April 1970 came from their demonstration of unity.