By Richard Ladle, Paul Jepson & Ricardo Correia

Nature conservation was one of the defining cultural forces of the 21st century but there are indications that its influence is waning: research suggests protected areas are under pressure to justify their existence in the face of competition with other land uses and that societies as a whole are becoming less interested in nature. In his STEPS seminar Bill Adams reminded us that “Conservation is never anything but social and never anything but political”. This generates two imperatives for conservation in the future: 1) to proactively engage with the information revolution in order to keep conservation visible in today’s fast-paced world, and; 2) to reinvigorate and demonstrate the popular support for conservation to underpin its cultural and political influence.

Our ability to do the latter has been constrained by the difficulty and costs of surveying people regularly and at sufficiently large scales. The good news is that people leave clues to their interactions with nature when they communicate with each other – through books, websites, facebook posts, tweets – and through their digital footprint (e.g. search histories on Google). Since words are symbolic representations of concepts, places or objects, the frequency with which words and phrases are used within these communication platforms provides information into human cultures and how they change. The formal study of human culture through the analysis of changes in word frequencies in large bodies of texts is known as culturomics.

In an article published this month in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment we argue that culturomics holds the key to understanding and potentially shaping human interactions with nature. We identify five key areas where culturomics can significantly contribute to conservation practice:

- Demonstrating public interest

Conservation needs to show that people are interested in environmental issues if it is to grab the attention of politicians and decision makers. Culturomic methods can be thought of as a form of polling, though one that does not actually ask any direct questions. For example, Eric Phu used culturomics to extract information from 1.2 million (!!!) conversations on the Chinese equivalent of Twitter (Sina Weibo). He clearly demonstrated that, contrary to popular opinion in the West, Chinese citizens care deeply about the environment and are generally against the use of elephant ivory.

- Identifying Conservation Emblems

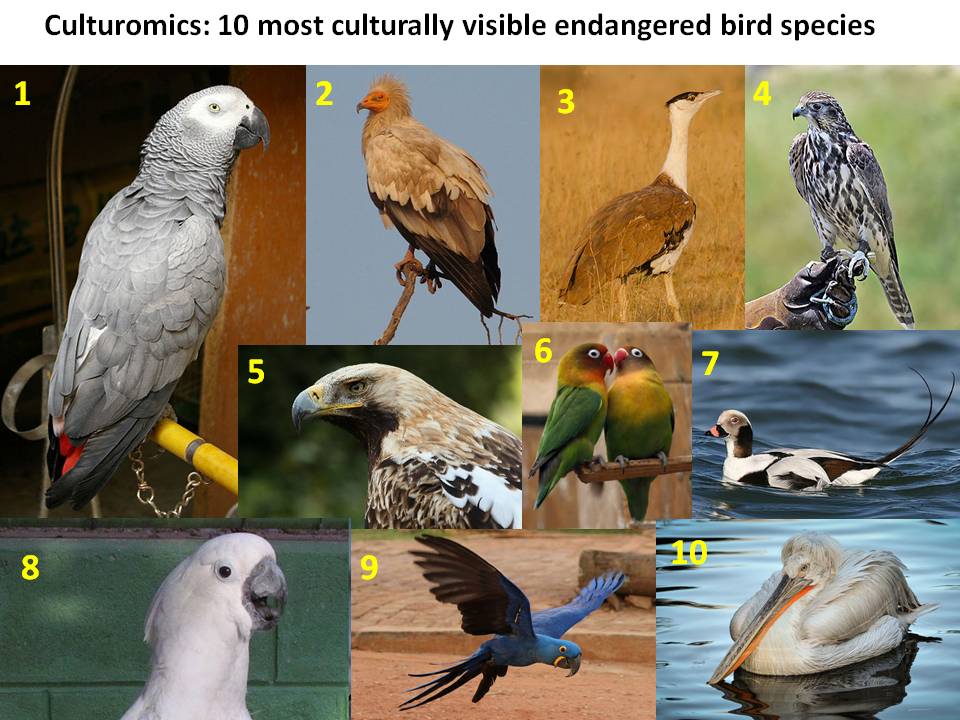

People value what they know, and societies act to conserve heritage. Iconic and emblematic species are one of the most important ways that conservation can connect with society, mobilizing support for conservation, providing a sense of nation, and stimulating people’s curiosity and wonder. Culturomics allows us to systematically assess the cultural visibility of species and, potentially, identify new or under-utilized icons, emblems or flagships.

- Environmental monitoring and valuation

When someone searches or posts something on the internet, it often contains valuable information about the state of the environment. For example, the frequency and geographic distribution of internet searches for hay-fever medicine tells us something about the prevalence of pollen in the atmosphere. It’s also not just common species that turn up on the internet: a new species of sundew was recently discovered on facebook! More seriously, scientists have been able to track and quantify illegal hunting behaviour by searching for videos on youtube.

The above studies are just the tip of a huge iceberg. With the increasing use of the GPS feature on smartphones, in the future culturomic analysis will allow us to find out both where and how people are enjoying nature – vital information for effective management.

- Cultural Impact of Conser

vation

vation

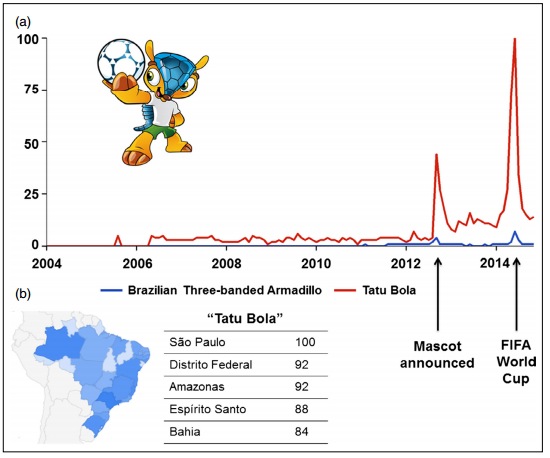

Conservation initiatives achieve greater success when they attract public interest. However, in the past this has often been hard to measure and was rarely investigated. Culturomics offers a cheap and powerful way to gauge public reaction to conservation events such as species reintroductions, new conservation flagships or the unveiling of a new protected area. A simple example is the impact on cultural awareness of choosing a nature-based mascot for a mega-event: there was a large increase in Google searches (in English and Portuguese) for the Brazilian three banded armadillo (Tolypeutes tricinctus) when it was initially unveiled as the mascot for the 2014 FIFA World Cup and when world cup was being played. Partly spurred by the increased public concern, the Brazilian government quickly designated a new wildlife reserve for this charismatic little species.

- Issue Framing

How something is understood by the public determines both the solutions deemed appropriate and how widely it is adopted. Conservation thus needs to have a good handle on public understanding if it is to maximize its societal impact. For example, culturomics shows that although the idea of the “balance of nature” still resonates strongly across societies, it no longer forms part of scientific discourse).

The future

Culturomic methods are incredibly powerful tools for investigating human interactions with nature. However, there is a catch – many of the databases that we would like to use are only available through third parties (e.g. Google searches) that were not designed for scientific analysis. Indeed, a simple search for the relative frequencies of the names of different bird species on web pages requires various technical steps such as disengaging the ‘personalization’ built into all commercial search engines.

In contrast to traditional survey approaches, culturomics research does not really deal with ‘raw data’ – it uses information produced from the interactions between humans and digital-machines. As yet little is known about these interactions, though there are academics around the world who are intensively studying all aspects of these issues. We would strongly urge conservationists to join this inclusive research programme, to use culturomics to explore the digital world. By doing so we can generate insights into not only how cultures interact with nature, but how these interactions are changing in time and space.

You can read our paper by clicking on the following link: Ladle RJ, Correia RA, Do Y, Joo G-J, Malhado ACM, Proulx R, Roberge J-M, Jepson P. 2016. Conservation culturomics. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14:269-275.

Republish this article

We believe in the free flow of information. We use you can republish this articles for free, online or in print in accordance with Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence