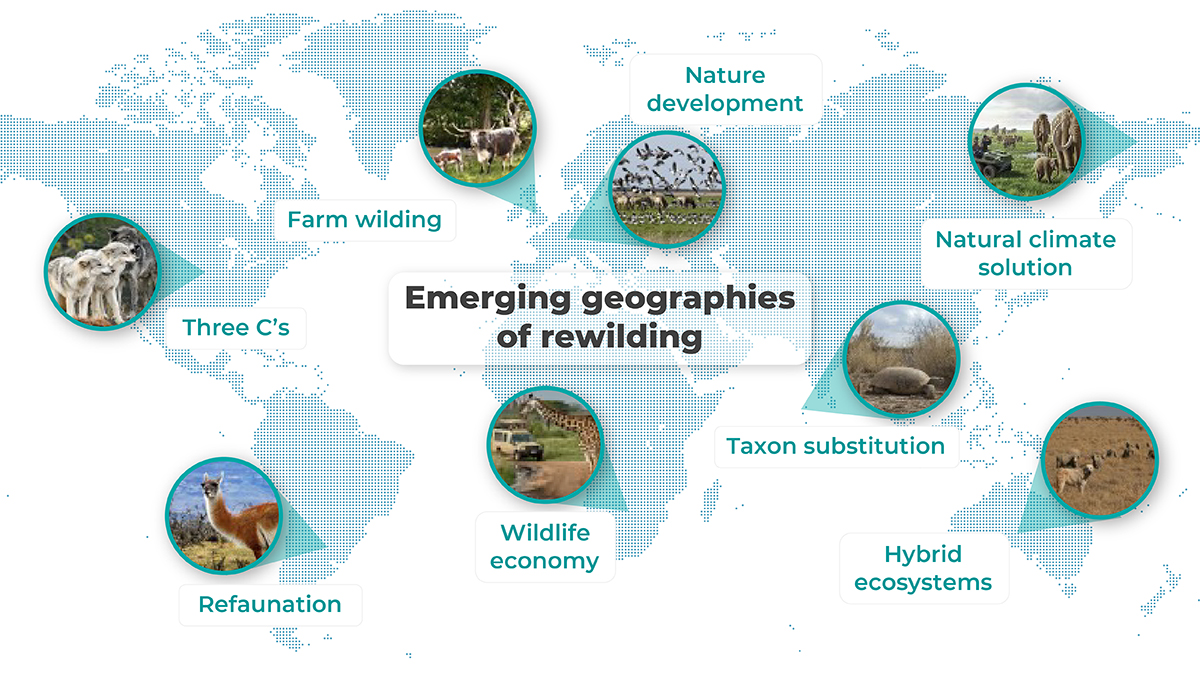

As a geographer I thought I should take the opportunity of the first World Rewilding Day to offer up this brief tour of different versions of rewilding that are emerging around the world. All express the paradigm shift in conservation from managing things – species, habitats and sites – to a focus on restoring the ecosystem interactions that give rise to vibrant, self-willed natures. These different versions of rewilding reflect the cultural, environment and policy context of their emergence. All are radical, entrepreneurial and effective. In my view they signify the emergence of a new conservation fit for the 21st century: a phenomenon that we should celebrate, support and invest in.

Three ‘C’s rewilding

The term rewilding was coined in 1992 by a group of US conservation biologists led by Dave Forman. It was linked to a continental-scale agenda to restore self-regulation ecosystems through the creation of large wilderness complexes with top predators able to reassert what are called ‘top-down’ trophic controls. This refers to the effects of predators, such as wolves, on the grazing behaviours of mega-herbivores which in turn effects vegetation structure and patterns and the abundance and distribution of different species. The agenda focused on the protection and maintenance of wilderness ‘Cores’, the creation of connecting ‘Corridors’ and the recovery or reintroduction of ‘Carnivores’.

The term rewilding was coined in 1992 by a group of US conservation biologists led by Dave Forman. It was linked to a continental-scale agenda to restore self-regulation ecosystems through the creation of large wilderness complexes with top predators able to reassert what are called ‘top-down’ trophic controls. This refers to the effects of predators, such as wolves, on the grazing behaviours of mega-herbivores which in turn effects vegetation structure and patterns and the abundance and distribution of different species. The agenda focused on the protection and maintenance of wilderness ‘Cores’, the creation of connecting ‘Corridors’ and the recovery or reintroduction of ‘Carnivores’.

Nature Development

Independent to developments in the US, the Dutch embarked on a radical new conservation agenda during the 1980s, termed nature development. Like the US rewilding agenda this sought to create ecological networks connecting the county’s few remaining natural areas. Unlike the US, Dutch rewilding started as an innovation in conservation practice led by a group of radical young ecologists within the Dutch nature conservation agency. Their observations of the spontaneous emergence of an ecosystem on a recently reclaimed polder, and in particular the role of grazing geese in steering recovery pathways, inspired a proposal to explore what would happen if natural grazing dynamics were restored through introducing and ‘de-domesticating’ ponies and cattle as proxies for Europe’s lost mega-herbivores guilds.

The Oostvaaredersplassen (OVP) reserve can be likened to the ‘punk rock’ of conservation – unsettling, inspiring, influential but ultimately too controversial to survive in its original form. But even as the OVP was getting off the ground, Dutch conservationists were developing a ‘second generation’ version of rewilding that blends ecology, pragmatism, entrepreneurship and compelling stories of future natural assets that could offer innovative solutions to climate change and enhance life-quality. For example, the rewilding of the River Waal reduced the risk of flooding to the city of Nijmegen, created a 20-year supply of clays and silts for the brick industry and lead to a remarkable and unexpected recovery of riverine ecosystems and species. Over a 20-year period the 3000 ha Gelderse Poort rewilding area has emerged and now supports a thriving recreational economy. This version of rewilding led to the formation of Rewilding Europe. It is the version that inspires and motivates me.

Wildlife Economy

European rewilding takes inspiration model of conservation that emerged in South Africa after the end of apartheid. President Mandela recognised that wildlife was part of the nation’s heritage but also that his administration had to attend to other pressing political priorities. He asked the private sector to help recover the country;s depleted wildlife and to enable this legis

lated that wildlife was the property of whoever’s land it was on. This led to the conversion of farms to game reserves with business models based on safari and game hunting tourism, wild meat and animal sales. Private game reserves now amount to 6-8% of South Africa and while most are fenced and the populations of large mammals managed to varying degrees, the ecosystems are functioning, full of life and have helped bring peace, jobs and prosperity to rural areas.

Experimental rewilding and natural climate solutions.

A forth version of rewilding is the large scale science experiment of which the Pleistocene Park in northeast Siberia is the most famous and audacious. I was fortunate enough to be part of a scientific team that travelled to the park in September 2019 to meet with Nikita Zimov who now leads the project started by his father Sergey in the mid-1990s. Through his research on permafrost, he realised that the sudden demise of mammoths and other mega-fauna ~10,000 years ago initiated a ‘phase shift’ from a steP grassland ecosystem to a boggy tundra system. In the absence of grazing and trampling, annual vegetation growth rapidly accumulated as frozen, carbon rich, soils. The high arctic is warming faster than anywhere else on the planet causing the permafrost to thaw and release worrying amounts of greenhouse gases. The Pleistocene Park is testing the hypothesis that grasslands can be recreated through a mix of mechanical clearing and large herbivore introductions, and if successful whether these grasslands will create colder winter conditions that reduce thawing and the release of greenhouse gases.

A forth version of rewilding is the large scale science experiment of which the Pleistocene Park in northeast Siberia is the most famous and audacious. I was fortunate enough to be part of a scientific team that travelled to the park in September 2019 to meet with Nikita Zimov who now leads the project started by his father Sergey in the mid-1990s. Through his research on permafrost, he realised that the sudden demise of mammoths and other mega-fauna ~10,000 years ago initiated a ‘phase shift’ from a steP grassland ecosystem to a boggy tundra system. In the absence of grazing and trampling, annual vegetation growth rapidly accumulated as frozen, carbon rich, soils. The high arctic is warming faster than anywhere else on the planet causing the permafrost to thaw and release worrying amounts of greenhouse gases. The Pleistocene Park is testing the hypothesis that grasslands can be recreated through a mix of mechanical clearing and large herbivore introductions, and if successful whether these grasslands will create colder winter conditions that reduce thawing and the release of greenhouse gases.

As rewilding science experiments go the Pleistocene Park is without doubt the most ambitious, but experimental rewilding areas are beginning to emerge around the world is scientist seek to understand the ecological effects of restoring lost megafana and the potential of rewilding as a natural-climate solution.

Taxon substitution

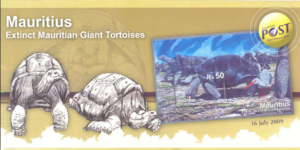

This is perhaps more a rewilding technique than a rewilding model. It refers to the introduction of substitutes to fulfil the ecological role of extinct species. The approach was pioneered on the island of Ile aux Aigrettes in the Indian ocean where Aladabra giant tortoises – the world’s only surviving island megafauna – from the Seychelles were introduced to replicate the grazing of the extinct Mauritian giant tortoises. This act was controversial at the time because it represented a shift from a focus on reducing directs threats to endangered species (mostly controlling non-native species that had jumped ship) to restoring proxies of extinct ’ecosystem engineers’ that created the ‘ecospaces’ where endemic island species evolved and thrived. The notion of taxon substitution which is now widely discussed in rewilding circles captures the distinction between what is termed the ‘compositionalist’ approach to conservation (protecting and manging units of nature) with the ‘functionalist approach (restoring ecological interactions so nature can lead) that characterises rewilding.

Taxon substitution ideas a ppeal to me because they seem to align with a core value of the English premier league, namely ‘colour and background doesn’t matter, all that matters is can you play?’ In my book Rewilding: the radical new science of ecosystem recovery I predicted that in the next 10 years would see the rise of ‘extreme rewilding’ where scientists experiment with introducing nearest equivalents. For example, elephants to South American forests or cheetahs to the American prairies.

ppeal to me because they seem to align with a core value of the English premier league, namely ‘colour and background doesn’t matter, all that matters is can you play?’ In my book Rewilding: the radical new science of ecosystem recovery I predicted that in the next 10 years would see the rise of ‘extreme rewilding’ where scientists experiment with introducing nearest equivalents. For example, elephants to South American forests or cheetahs to the American prairies.

Refaunation

Reintroducing species that have become locally extinction is a well-established conservation technique. The refaunation version of rewilding extends this by actively resembling guilds of lost large mammals to restore ecosystem processes. It is similar to taxon substitution but with a focus on native species. The Ibera project in Argentina is the flagship initiative and has involved the reintroduction of giant anteater, tapir, peccary ad jaguar into private lands adjoining the Ibera national park. This rewilding resulted in the national park upping its conservation ambition.

Hybrid Ecosystems

Rewilding in Australia is super complex. Passive rewilding – simply removing agriculture and letting natural vegetation recover – could be good for biodiversity but massively increase the risk of wildfires. The continent’s marsupial megafauna is long gone, all mega-herbivores are introduced, and large predators are absent. Restoring functioning ecosystems will require ‘rewilding by design’ and the assembly of ‘hybrid ecosystems’ from a blend of native, non-native, feral and introduced taxon substitutes. This version of rewilding needs creative, yet cautious and careful thought, not least because it would involve consciously setting Australian nature on a new evolutionary trajectory.

Farm Wilding

Photo: Matt Ellery

The most recent version of rewilding and one that is capturing the public imagination in England is farm wilding. This expresses the positive pragmatic ethos of rewilding, namely ‘rewild within the constraints of what is possible’ and the recognition that when it comes to nature recovery moving up from 1-3 on a rewilding scale is just as good as moving from a starting point of 7 to 9. Farm rewilding involves relaxing or removing the agricultural infrastructure and practices that ‘forced’ ecosystems to produce commodity crops and livestock. As nature begins to ‘kick back’, natural grazing is introduced using primitive breeds of cattle, ponies and pig and new farm business models developed based on revenues from a mix of experiential recreation, premium meat, the sale of natural capital credits and/or public payments for the ecosystem services. This version is still in its infancy, but Rewilding Britain has recently launched a network of over 40 pioneering initiatives. For me, farm wilding evokes an older vogue for model farms where enlightened owners demonstrated new approaches and techniques in so doing promote public discussion and reflection on the future of agriculture.

I hope this brief, and no doubt incomplete account, of the geographies of rewilding has illustrated the variety of rewilding approaches around the world. There is a lot of flow of ideas between the different initiatives but in my view there will never be one version of rewilding. Context matters: environmental, cultural, political and scientific histories and agendas influence the way rewilding principles are expressed in space and time. A diversity of rewilding approaches offers the prospect of rich and diverse planet.