During the lockdown summer of 2020 an immature bearded vulture took up residence in a rugged Valley of England’s Peak District National Park. On a September Sunday, my birding buddy Steve and I set out at the crack of dawn and programmed WAZE to navigate us North. Three hours later we descended a windy road across a bleak rain swept moor to a carpark where birders shouldering scopes and tripods confirmed we were in the right place. “Do you know if it’s been seen today? What are the directions?”, we asked. “Yeah, up the track, turn left through the gate and head up the Valley. You’ll see the assembled birders”, was the helpful reply.

We headed out the car park and through the gate. Looking up and – “goodness there it was, wow!” – drifting just above us over a low ridge. It landed on a boulder pinnacle and through our scopes we could see the downward pointing feather tufts from which it gets name (more a moustache than a beard though). After a few minutes it took off and glided out of view. We climbed the ridge and had more glorious views as it circled overhead. Someone rumoured that a photographer had put out some chicken bits on a photogenic rock.

We headed out the car park and through the gate. Looking up and – “goodness there it was, wow!” – drifting just above us over a low ridge. It landed on a boulder pinnacle and through our scopes we could see the downward pointing feather tufts from which it gets name (more a moustache than a beard though). After a few minutes it took off and glided out of view. We climbed the ridge and had more glorious views as it circled overhead. Someone rumoured that a photographer had put out some chicken bits on a photogenic rock.

Standing around waiting for it to reappear we fell into conversation with a young birder from the Wirral as we gazed up the valley towards a distant group of birders hoping for the sort of views we had just enjoyed. It soon became clear that our new friend was a serious twitcher, recently back from Shetland and happy to recount the list of ‘megas’ [extreme rarities] he had seen. I have always been a bit of a twitcher but for the last decades a combination of family, funds and work has limited my range to day trips from Oxford.

What counts as wild?

I have a longstanding interest in the birds that the twitcher community does and does not consider tickable. Clearly, we can’t include captive and escape birds on our British lists, but the boundaries of what counts as wild are blurred. Back in the 1980s this decision was made by a rarities committee and to an extent it still is. At one stage they were pretty extreme, debating whether a ship-assisted vagrant could be classed as having ‘naturally’ occurred in the wild and therefore added to Category A (gold standard tick). The response of our new friend to my question “do you think we can tick it [the Vulture]” was simple. “Its quality, I can’t believe I’m watching a lammergeier in England. I saw it a couple of weeks back but wanted my girlfriend to see it”. His was the response of younger generation twitcher for whom the experience, the event and the story was what mattered: not the decision of a committee.

His response may also reflect a change in conservation culture over the last 50 years. In the 1980s, the approach of conservation agencies, such as the RSPB, was to create habitat suitable for rare species and hope they would recolonise unassisted. The slow recovery of bittern populations in response to reedbed creation is emblematic of this approach. However, the 1980s also saw zoos becoming more focused on field conservation and developing techniques to captive breed and release endangered species into their former ranges. Today, the breeding and introduction of species is increasingly common place and an important aspect of active rewilding.

That evening I did some web research on the day’s’ ‘big bird’. I quickly found the website of the Vulture Conservation Foundation, who politely asked that people stop referring to the species by its old name lammergeier, which means lamb vulture (i.e. killer) in German, and instead adopt the more neutral name bearded vulture. An informative article explained that because the vulture I had seen lacked tags or marking it was a wild hatched bird coming from captive-bred parents reintroduced in either the Alps or Pyrenees. Typically, birders don’t count individuals from reintroduction programmes on the lists until a wild populaton has become self-sustaining: in England the great bustard and white stork are examples of introduced species that have not yet reached this status.

The VCF website also explained that it was normal for immature bearded vultures to roam northwards from the Alps and Pyreness. In October, the Peak Distruct the bearded vulture stated heading back south and on 14th a birder at Beachy Head in Sussex saw it heading out to sea. After 30 minutes it turned back but then caught another thermal soared upwards and tried again. It was later reported in Belgium. As a rewilder I found this event hugely symbolic. It proved that the English Channel is no barrier to vultures and, by implication, they could once have been part of our British fauna and could be so again.

A new conservation ambition

Five months later , Cain Blyth, Ecosulis managing director, and I were driving back from an estate in Yorkshire that is pioneering a rewilding enterprise approach. Or conversation moved to the topic of the company’s new website. Our marketing agency had designed a striking ‘hero’ homepage with a split circle that combined a built world and a bird’s eye image to represent our company’s mission to help rewild half the world. They had used a pigeon eye and Cain described how he felt this was visually bland and searching ‘bird eyes’ on the web had come across the cool-looking eye of the bearded vulture. This prompted me to share my twitching tale and we realised that the bearded vulture beautifully symbolises our rewilding ethos and ambition.

Our journey down the M65 and M6 took us through landscapes largely sanitised of wildlife by the practices of industrial food production. Our government’s stated ambition to ‘leave nature in a better place than we found it’ expresses the rewilding movement’s vision to move beyond a defensive focus of nature protection towards a proactive agenda of nature recovery. Unfortunately, conservation technocrats in government tasked with implementing this ambition, have stayed with the 1980s approach and designed policies to simply extend the area and quality of different habitats.

A key insight from rewilding theory is that biodiversity, wildlife abundance and ecosystem resilience are all emergent properties of dynamic interactions between the tropic complexity (the web-of-life), different forms of natural disturbance and the ability of organisms to disburse over time and space.

Unfortunately, in UK policy the concept of habitat has been reduced to associations of plant species that were characteristic of pre-mechanised agricultural landscapes. These have some wildlife value but are nowadays static, highly managed, isolated and support a ‘flattened’ web-of-life. We now understand that modern ecosystems evolved from the dynamic interactions between megaherbivores, grassland and woody vegetation and natural disturbance.

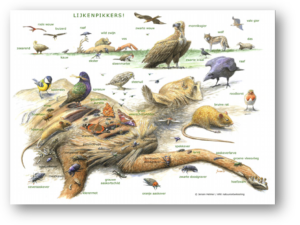

Reassembling guilds of mega-herbivores, where possible, is central to the rewilding  approach. Cattle, horses, deer and pigs create natural disturbance through their trampling, scuffing, rooting and browsing, they transport seeds in their fur and organisms in their guts, and their dung and carcasses input nutrients and carrion into natural systems. In short, megaherbivores expand ecospace (microhabitat) diversity and enable ecosystems to expand.

approach. Cattle, horses, deer and pigs create natural disturbance through their trampling, scuffing, rooting and browsing, they transport seeds in their fur and organisms in their guts, and their dung and carcasses input nutrients and carrion into natural systems. In short, megaherbivores expand ecospace (microhabitat) diversity and enable ecosystems to expand.

For rewilders the ambition to ‘leave nature in a better place than we found it’ signifies more than simply improving our stocks of habitat on a balance sheet. For rewilders better means healthier and our ambition is to restore nature as a force that can interact with the forces of technology, economy and society to create a better future for all – people and nature.

In Britain the forces of nature are at a very low ebb, but rewilding projects are demonstrating the capacity of ecosystems to recover. We are motivated to create the conditions where British ecosystems move to into a phase of self-recovery and reassembly and a time when scavengers, such as the Bearded vulture appear and settle in our country.