In March I introduced my students to protected area professionals working to conserve the unique biodiversity and landscapes of Tenerife -Europe’s popular vacation island located off the north coast of Africa.

Tenerife is becoming a city island. It has developed rapidly since the rise of package holidays in the 60’s and nowadays receives upwards of five million tourists a year.

I my mind the island’s protected area system has to rate as one of the best examples of state-led conservation anywhere. Here are five reasons why.

1. Fantastic planning

The system was developed in the 1980s guided by the principles of representation, endangered species conservation and nature for people expressed in a seven functional protected area designations that cover half the island.

Jorge Bonnet, Head of Biodiversity for the Cabildo de Tenerfie (island administration) explained how this system created a clear zoning between land for economic development and lands for natural resource conservation. Within this basic division the range of PA designations empowers the administration to adopt a ‘gradated’ approach from strict protection where necessary to conservation-friendly agriculture and tourism where this is suitable.

The Cabildo’s PA planning extends well beyond the spatial component. We spent a lot of time talking about how the island government was embracing moves to decentralize the governance of individual PA units, including Teide National Park, and how early on it invested in building internal capacity to secure European Union and other funds to invest in the system.

2. Sustained stakeholder engagement.

This is happening at all levels but a best practice example is the Teno Alto Rural Park in the east of Tenerife. Enrique Simo Perez director of the park since 2000 spoke to us about the formation of a governing council involving government officials, scientists and local residents who developed the park management plan and now oversee its implementation. This governance model is simultaneously generating sustained socio-economic benefits for villagers, enhancing the conservation of rare species and extending nature-based tourism on the island

3. Research on complex management challenges.

Climate change has allowed rabbits to ascend the slopes of the famous Teide National Park and colonize the volcano’s crater. Jose-Luis Esquivel showed us his plots where he is researching the impacts of this new dynamic on the native fauna.

He talked about the difficulty of devising management solutions in a situation where data on past vegetation base-lines is lacking and climate futures are uncertain. It was great to see a parks service grappling with complex management challenges through a sustained programme of research.

4. An ethos of restoration

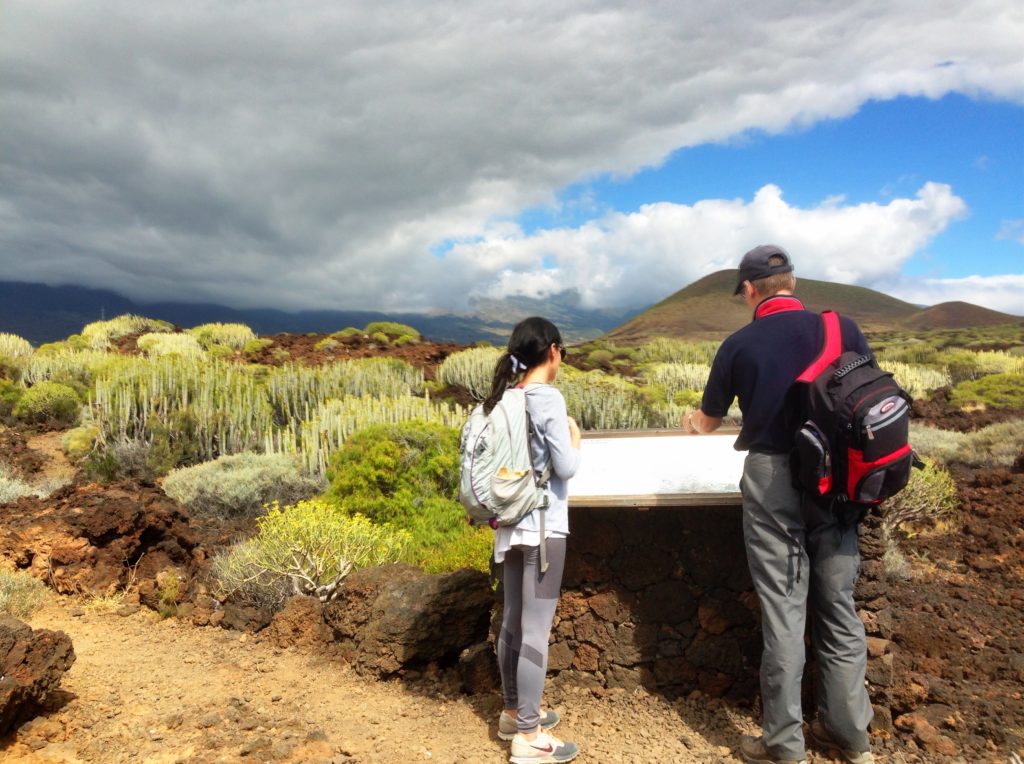

Monitoring vegetation restoration in Teno Alto rural park

This is embedded in the government’s conservation approach. We spent an afternoon monitoring the growth of trees planted to restore an area of native thermophilous woodland at Teno Alto and visited a the restored cinder cone of Monatana Amarilla and lava flow of Malpias de Guimar.

The quality of the government’s restoration work is evident at Guimer. Working within the framework of a one-off grant secured from the EU they have executed an unobtrusive landscape design that effectively channels local joggers, dog walkers and visitors along a few routes thereby allowing the fragile vegetation to recover.

Importantly they weren’t too purist about the restoration. They allowed a collection of beach retreats within the special protection area to remain and in so doing have maintained the good-will of the adjoining community.

5. Openness to grass-roots innovation

In 2006 David Novillo, owner of a dive company in the municipality of Adaje, created a social enterprise, Oceano Sostenible, to rid El Puertito of the lime urchins which have devastated the cove’s marine ecosystem. With passion and panache he told us how he’d enrolled local hotels to fund dive courses for local residents who in return committed dive hours to destroying the urchins, how he marketed introductory (flyover) dives to tourists so he an his team could monitor and care for the recovery, and how he built enthusiasm for his project through a schools education p rogramme.

rogramme.

The cove quickly recovered its ecology but this attracted divers and dive boats from far and wide causing injury to the returning green turtles as well as public safety risks The municipality stepped in to support David’s initiative and is using its access and influence to create a form of conservation concession – a pioneering new type of protected area for Tenerife and indeed Spain. Plans are afoot to extend the marine restoration to adjacent cove of La Caleta.

Tenerife’s reminds us that public conservation agencies bring an awful lot to the table: leadership, expertise, pragmatism and dedication along with the authority to plan, access funds and establish partnerships. On Tenerife these attributes have created a protected area system that is comprehensive, progressive and resilient, In short, world class.