Good morning all, and thanks for the invitation to present today.

Gary asked me to present some thoughts on new paradigms for conservation. My aim is to do just this. I will argue that we need to seize the opportunity of Brexit to reframe how we think and talk about rural lands.

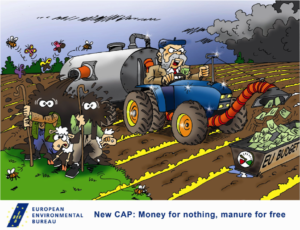

Brexit is a reality whether we like it or not. Brexit also means CAPexit. Keeping CAP can hardly constitute the withdrawal from the EU that the majority of farmers voted for.

Brexit is a reality whether we like it or not. Brexit also means CAPexit. Keeping CAP can hardly constitute the withdrawal from the EU that the majority of farmers voted for.

Brexit and CAPexit, amount to what we in academia term “critical junctures” or periods of “institutional fluidity”. They represent opportunities to bring about fundamental shifts in the underlying logics of the structures that govern – that constrain or enable what we can and can’t do.

Periods of institutional fluidity are rare – the last really big one was WWII. Brexit is similarly big and we, as a conservation movement, must mobilise to seize the opportunity to shape and steer post-Breixt institutional institutions that will structure our ability to conserve, restore and revitalise living landscapes.

We are in good shape to so. This because we know what we want. It’s long been known that with biodiversity and wildlife of a landscape is detemriend by the interaction of three components – or dimensions”

Composition: the species (units) and habitats (assemblies of species),

Composition: the species (units) and habitats (assemblies of species),

Structure: connectivity and patterns in the landscape, and

Function: ecological processes and dyanmics.

We now have the theory evidence and practical/management models for these three components. The first- composition -is where ecology was ‘at’ in the 1970 and this component shaped law and policy, and hence our conservation institutions.

The rise of GIS in the 1990s enabled science to tackle the structural component and this is reflected in the Lawton report and the principles underlying the Wildlife Trust’s Living Landscape approach.

In the last twenty years advances in computation and modelling have enable scientists to get their heads round the functional component. Interacting with this rise of ‘functionalist’ perspectives in conservation science we have seem the emergence of rewilding as a new and vibrant conservation approach with pioneering projects and initiatives.

On one, level the goal is to now integrate these three components, and in particular our improved understanding of the importance of ecosystem processes and dynamics, into nature policy. Last year, Frans Schepers, from Rewilding Europe and I, made a first step in this direction at the EC policy level. The officials in the Nature and Biodiversity Units, understandably asked Rewilding Europe to first coordinate our ‘asks’ with the conservation lobby in Brussels.

On one, level the goal is to now integrate these three components, and in particular our improved understanding of the importance of ecosystem processes and dynamics, into nature policy. Last year, Frans Schepers, from Rewilding Europe and I, made a first step in this direction at the EC policy level. The officials in the Nature and Biodiversity Units, understandably asked Rewilding Europe to first coordinate our ‘asks’ with the conservation lobby in Brussels.

This policy brief is the outcome of our ‘negotiations’ with the three big conservation lobby networks in Brussels and presents seven rewilding principles.

The process generated four insights, which I think are important in terms of looking ahead and which I’d like to share with you.

- Existing legal frameworks are generally unsupportive of ecosystem function – key instruments such as favourable condition are compositionalist in nature and for good reason – they enable strong and defenable. It is hard to specify and defend process and dynamics in law!

- Policy fear/institutional inertia – there’s a real worry that if we say we have a new way to do conservation the development and agricultural lobbies will turn it against us and argue that existing law should be relaxed.

- No mandate to lobby for ecosystem process and rewilding – our lobbyist in Brussels say they can discuss rewilding but they have no mandate from their member organisations – people like you to actively lobby for functional approaches to be include in future policy mandates.

- Conservation NGO business models- there seems to be a degree of lock-in to current stuctures and ways of doing things.

For me all of this adds up to aging environmental institutions. The question then becomes can we repurpose existing law and policy to create the living landscape we want in the mid-21st century or do we need to revist the underlying worldviews and logics on which they are built?

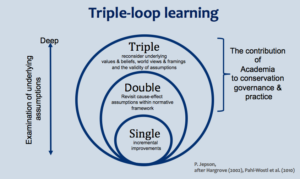

This is one of the first slides I show my MSc Biodiversity students. It is intended to position the contribution of academic ‘wing’ of conservation and to introduce where we will be taking them during the course.

This is one of the first slides I show my MSc Biodiversity students. It is intended to position the contribution of academic ‘wing’ of conservation and to introduce where we will be taking them during the course.

The insights I have just shared arise from trying to learn in the double loop. The negotiating bottom line of the Brussels green lobby was;

“protect the gains of the past and kick on”

This makes absolute sense but it also risk double-loop lock-in

If we are to seize the opportunity of Brexit and leverage the institutional fluidity we have entered I believe we need to boldly go into the triple loop.

I my view, the fundamental problem lies with our cultural and policy framing of rural lands.

When we think and talk about policy it is always in terms of:

farmland: fams: farmers: agricultural subsidies

This is a WWII framing of necessity, which we haven’t up-dated since.

I suggest we need to ditch this framing in favour of one of

Land assets: rural enterprises, entrepreneurs and investment

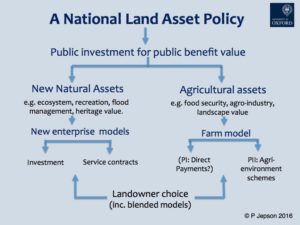

I would like to see our movement uniting to lobby for a national land asset policy to replace CAP.

This would be based on the principle of public investment for public value generation.

The concept of natural asset is introduced in detail, and compared with natural capital, in Jepson et al, (in press) Protected Area Asset Stewardship, Biological Conservation

It would broadly divide land assets into agricultural assets and natural assets. Agricultural land assets would receive pubic money where they can show they are generating public value in terms of food security, the production of crops with a strategic or social need and maintaining landscapes character. We could retain a version of CAP for such assets, at least during a transition period.

Natural land assets would receive public money for generating forms of public value in the form of, for example out-door recreation, ecosystem services, flood management, a sense of heritage and identity. Public money would be invested in enterprise – either as a contract to provide publics services that markets struggle to deliver or as investments for new nature-based enterprise.

Landowners, would have the choice of how, and if they want to use and develop their land assets for generating value.

This, in my view, would promote innovation in land management. For instance, you have been looking at the rewilding model here at the Knepp estate. The owner, Charlie Burrell has no option but to innovate within the constraints of the agrciultural farm policy model. This limits the sort of rewilding he can do and the value his efforts can generate for nature, people and the rural economy.

I do not think this idea of a National Land Asset Policy is fanciful and here are five reason why:

First, the UK government has consistently spoken against CAP and agricultural subsidies,

Second, it aligns with investment & enterprise policy narratives and the natural capital policy frame,

Third, I sense growing public awareness and disquiet at the social and environmental injustices in the agricultural subsidy regime.

Fourth, farmers know the quality of their work life is declining and they are looking for better alternatives,

Lastly, I can’t quite see how a public debate on how much to public money to spend on the NHS and farmers will wash politically.

Perhaps more importantly, framing land as a collective and individually-owend asset forces four fundamental questions:

- What forms of value are land assets currently generating and for whom?

- What forms of value could be generated from land assets and for whom?

- What forms of value are wanted, what are the trade-offs, and who decides?

- What forms of investments are needed to ensure that intended ‘publics’ can capture investment value?

Tackling such questions will introduce democratic debate and accountability into land policy.

I mentioned earlier that we – the conservation movement – have the models to demonstrate a new future for landscapes.

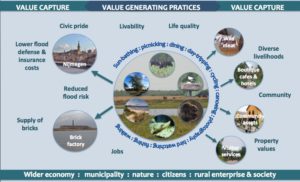

At Gelderse Poort in the Netherlands our Dutch colleagues have transformed agricultural assets along the River Waal into natural rewilding assets with amazing public value gains.

In brief, as you can see from this map the city of Nijmegen was on a nasty bend of the River Waal and massively vulnerable to flooding from higher peak flows resulting from climate change.

In brief, as you can see from this map the city of Nijmegen was on a nasty bend of the River Waal and massively vulnerable to flooding from higher peak flows resulting from climate change.

This project, designed and led by Wouter Helmer and the Ark Nature Foundation, involved buying agricultural land within the winter dykes and removing the summer dykes to widen the river corridor.

The old river meanders and profile have been restored through selling the silt to a brick factory which generated value for the Dutch constructing industry.

The new rivering lands we rewilded through the introduction of wilded pony and cattle heads, through the reintroduction of species such as beaver, white stork and even sturgeon. Sturgeon can you believe it! – the Dutch are so far ahead of us!

A whole load of spontaneous rewilding also took place. Black poplars once an endgared species in the Netherlands regenerated en mass and it was relased that their seeds need warm shallow summer water to germinate and this river habitat had all but disappeared in the Netherlands and indeed Europe. Another habitat that reappeared was river beaches and sand dunes.

Talk about reframing. Before I visited Gelderse poort I though sand dunes we confined to coasts!

The new natural assets of Gelderse Poort stimulated a range of value generating practice among the citizens of Nijmegan – some old such as cycling and bird-watching others new such as beach picnicking, sun-bathing and nature-photography. In turn, these practices constitute a cultural assets which entrepreneurs can monetise through new local enterprises such as botuique cafes and hotel and a wild meat company.

Twenty years ago the land assets along the Waal generated about 20 farm jobs: as a rewilding asset they are generating perhaps four or five times as many jobs, but more importantly diverse form of public benefit value – from reduce flood defence costs, to enhanced liveability for citizens and the recovery of wildlife and ecosystem processes.

This is the sort of post-Brexit vision we as a movement could be advocating for Britain.

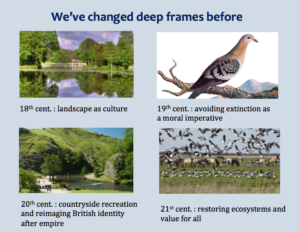

As a nation and culture we have change deep frames before. In the 18th century we made landscape cultural, in the 19th century we established extinction (avoiding the knowing extinction of other animals) as a moral steer for society, in the 20th century we established National Parks as part of the process of reimagining Britishness after empire.

As a nation and culture we have change deep frames before. In the 18th century we made landscape cultural, in the 19th century we established extinction (avoiding the knowing extinction of other animals) as a moral steer for society, in the 20th century we established National Parks as part of the process of reimagining Britishness after empire.

If the conservation movement is to retain its position as a cultural force in the 2ist century we need to mobilise to bring about similar shifts in the underlying worldviews that shape and steer policy and cultural institutions.

Brexit is our opportunity to do just this. To retire the idea that agriculture is the primary public purpose of land and replace this with a worldview that frames land as collective and individual assets that should be invested in to restore value for all – society and nature alike.