As part of the UK Green Film Festival last Saturday I was invited to be a discussant at the Oxford showing of Louie Psihoyos’ documentary ‘Racing Extinction‘.

The film is a visually engaging and emotive smorgasbord of environmental issues brought together under the narratives of extinction and the slaughter of sea-life, in particular sharks and manta rays. Psihoyos fronts the documentary as photo-journalist shocked into activism by the awfulness of how humans treat other life and the planet in general. It features activists filming under-cover conversations with wildlife traders, comments from prominent US conservation scientists, and the team engaging in high-tech direct action in the form of projecting extinction images and facts onto New York skyscrapers.

160 images of endangered species were projected onto the Empire State Building. Photo: Oceanic Preservation Society

As my opening remark I contrasted the simple, emotive & moralistic version of conservation presented in the film with the “how to act in a messy, networked, multi-cultural cultural world” version of conservation’ which I teach, and expressed my worry about the growing distance between the way media professionals present conservation to mass publics and how it is conducted in practice by conservation professionals.

The response from the audience was that grabbing attention is what matters: people need to be made aware. Ten years ago, newspaper headlines reported that climate change would cause ‘over a million species to go extinct…by 2050′. The scientific paper on which the reports were based said nothing of the sort, but when Richard Ladle and I published a paper arguing that sensationalising science could be counter-productive, the scientists and NGOs concerned responded by arguing that the media coverage generated was with the inaccuracies – 13 million people heard the climate change poses a serious risk to species.

I still don’t buy the argument that misrepresenting reality is okay if it grabs attention. How an issues is shaped for publics and policy determines the responses deemed appropriate and legitimate. Simple messaging can lead to ‘silver bullet’ solutions that may simply make people feel good rather than address the issue in an effective manner.

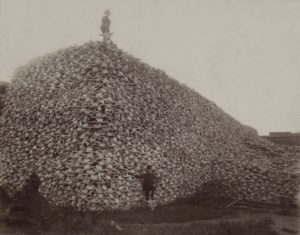

Bison skull pile, US 19th century.

In my second remark I was a little bit more ambitious. I attempted to position Racing Extinction in relation to two phases of 20th century extinction rhetoric. During the first, from around 1890 to 1940, blame for human-induced extinctions was placed firmly with white settlers such as the market-hunters of the US west and ranchers of Africa. In the second, which followed the 1970s ‘shock’ of environmentalism, blame was shifted to industrialists and the polluting, resource consuming and land -grabbing practice of their corporations.

Racing Extinction is consistent with an emerging narrative at the nexus of wildlife trade and animal welfare that shifts the blame back to certain groups within society, and in particular groups within Chinese, SE. Asian, and African society. My effort to contrast the tense, judgemental undercover engagements between activists and traders with the more genial negotiated engagements I experienced during my days working in Indonesia prompted two fascinating audience reactions.

Bird traders, hobbyists and conservationists come together in Java to understand where each other is coming from and explore ways to reduce the threats to wild bird populations caused by the cultural practice of bird-keeping.

First, I was asked whether I was suggesting the activists were being racist. At the time I didn’t know how to respond to this question. For me the over-riding narrative of Racing Extinction is one of ‘white crusaders bravely challenging people from other cultures whose values and practice conflict with their cause’. I don’t think this is racist but it does express a sense of superiority concerning the values held by the activists concerned. In my view effective conservation is about believing in the universal appeal of the core conservation values and ‘blending’ these with the values of other cultures through forms of engagement that build understanding, respect and reflexivity.

The second comment, was simply that an audience could hear and see the conversation between undercover activists and traders but couldn’t be witness to the type of conversations I had had with traders. This is so true, and for me underlines the skewed perceptions of conservation action that mass audiences get and the challenges of communicating the wider more nuanced picture.

This latter theme became more prominent when my co-discussant Helen Buckland from the Sumatran Orangutan Society and I offered a more hopeful narrative of efforts to avoid extinctions drawing on examples of success. I heard myself explaining how the sixth extinction crisis was an imaging generated by extinction forecasting science that had lead to a massive expansion of protected areas globally and thought ‘how could this story translate into a compelling, oscar nominate-able documentary?’

I came away from the Ultimate Picture Place pondering on a question that is beginning to bother me. Is it possible to frame a different story of conservation to a mass audience? One that tells how in the face of rapid population growth and the dominance of market-economics, the conservation movement has achieved remarkable success. Okay we have lost the baiji and amphibians are suffering many extinctions, but we avoided the extinction of the African mega-fauna, the Golden lion tamarin has gone from 200 to 3200 individuals, the majority of known terrestrial species now occur in protected areas, and the auroch has been ‘de-extincted‘!

Ten years ago the UK Institute of Public Policy Research published a highly regarded study on the impact of sensationalist doom and gloom climate messaging and dubbed much of it ‘climate porn‘ – media that arouses emotion but doesn’t lead to meaningful action.

It seems to be that when it comes to conservation communication we do the two ends of the spectrum well: sensationalist documentaries and deep academic articles, but we have yet to find a way to grab people’s attention and then take them on a journey of deeper understanding. It is important to do so because effective communication and effective policy go hand-in-hand.