Back in March I was asked to provide a conservation perspective on the topic of “A homogenous world: Global culture and the future of mankind” at Oxford’s 21CC debates

I contributed these reflections from my career.

When I was a young man in the 1980s I travelled the world motivated by my passion for birding and guided by an interest in nature conservation.

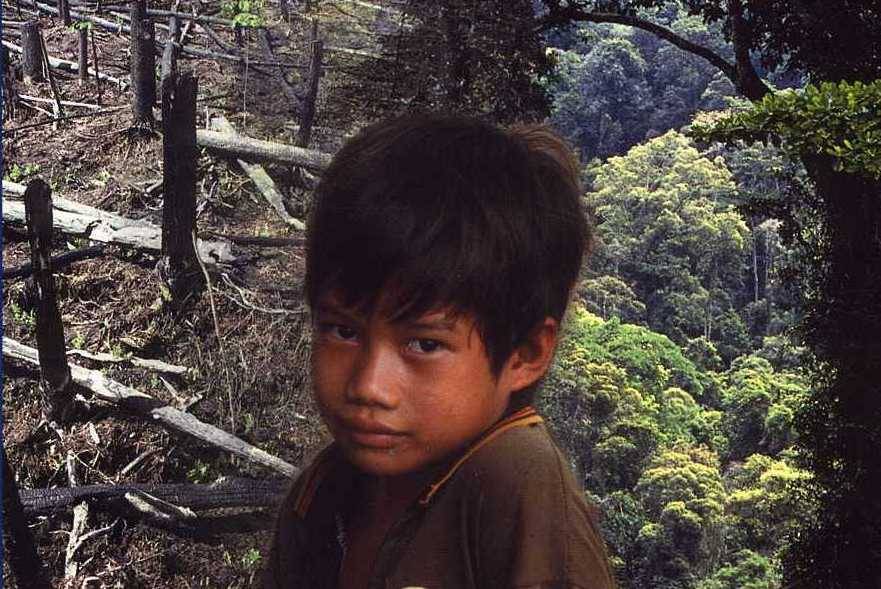

I experienced many cultures of conservation – ways of knowing and engaging with nature and conserving natural assets. In Yorkshire where I grew up, I participated in the English ‘gardening’ approach to habitat restoration performed by a bird charity. In the Alps I experienced recreation-led conservation shaped by European Alpinism. In India I connected with the idea of giving sanctuary to wildlife lead by a specialist bureaucratic elite. In Thailand I encountered jungle reserves that local people and I were a little scared to enter.

I experienced many cultures of conservation – ways of knowing and engaging with nature and conserving natural assets. In Yorkshire where I grew up, I participated in the English ‘gardening’ approach to habitat restoration performed by a bird charity. In the Alps I experienced recreation-led conservation shaped by European Alpinism. In India I connected with the idea of giving sanctuary to wildlife lead by a specialist bureaucratic elite. In Thailand I encountered jungle reserves that local people and I were a little scared to enter.

This was a diverse and colourful nature conservation.

In 1991 at the age of 31, I moved to Indonesia to set up the BirdLife Indonesia Programme and during the following 12 years became part of a technocratic homogenization of nature conservation.

In the rugged uplands of Europe conservation is integrated with out-door recreation

International development policy doesn’t do outdoor recreation, national beatification, iconic species and conservation ethic. These goals, expressed differently in cultures for near on a century, had created the diverse geographies of conservation that I had experienced during my youthful travels.

International development does resource management, livelihoods and poverty alleviation. To translate nature conservation into a high-level policy force that could align with these goals conservation scientists coined the term biodiversity and standardized nature into units that could be accounted and managed for in a strategic way: species richness, endemism and endangerment. This process of technocratic homogenisation aligned conservation with the resource management ethos of international development and created the possibility to imaging that these units of nature could somehow improve the lot of poor people living in bio-diverse regions. It generated major new funding flows that financed a major expansion of protected areas in less developed countries. Unfortunately it also led to disconnect between conservation science and policy and the cultural context of its expression.

Now I am beginning to see a moral homogenization of conservation associated with the rise of terms such as ‘legality’ and ‘corruption’. Simplistic, black & white rhetoric such as the ‘War for Wildlife’ has conflated the ancient and varied practice of trading wildlife into a simple story of wildlife enforcers struggling to stop poaching of iconic by organised crime and terrorists factions.

Such narratives have populists appeal, particularly among urban people, but the are manifesting in a top down calls for ‘stricter enforcement’ everywhere – the use of a blunt moral hammer that can crush the embedded knowledge of situated conservationists and with this the potential to find solutions that mobilise local cultural assets and achieve lasting impact.

My worry is that we are witnessing the emergence of a dominant, almost imperialistic narrative of how others should relate to nature and how it should be conserved. Put another way we are loosing the idea that if conservation is to become a cultural force them policy and action needs to be co-produced in different settings and this will result in different ‘shades’ of conservation globally.

I moved to Indonesia in 1991 because the Suharto regime was under heavy criticism from the international community for trading parrots out of East Indonesia without having conducted ‘non-detrimental’ findings as required by CITES. In those days the ethos of conservation was one of working together to sort out problems. I moved to Indonesia as a representative if an international conservation network, alone and with the aim to understand and find a way ahead rather than to judge. In short, to build trust between different cultures of conservation.

A progressive and influential concept of the 1990 but one that gave equal weight to endemic species irrespective of their cultural profile.

The technocratic standardisation of nature conservation has contributed to an undermining this dynamic of trust. Standards are agreed – for Key Biodiversity Areas, Forest Certification and for what constitutes sustainable off-take – that can be assessed by consultants. In this governance mode there is no need for resident expatriate conservationists able to develop deep professional relations with national conservationists and challenge and unsettle the views of their head of office colleagues in Cambridge, Washington or New York.

But I am an optimist. The processes described above are, I believe, manifestations of last 20th century internationalism. In my view the internet and the role out of computing as a utility will lead to a return to the diverse geographies of conservation that were the norm up until the 1980s. This is because I don’t think they ever really went away, I think they were just obscured or over-written by a homogenised biodiversity policy discourse.

New technological forces release grounded conservationists from the need to adopt a internationally negotiated narrative of conservation in order to gain access to funding, decision-makers, data & analytics, networks and so forth. Nowadays anyone with a laptop and access to the internet can assemble the networks and investment to do conservation in their way.

The beginnings of these new geographies of conservation are already beginning to emerge: rewilding in Europe and wildlife ranching in Southern example are two example of new forms of conservation rooted in the cultural trends and values of their regions.

In my view the future of conservation is a return to heterogeneity. This is because nature is cultural and therefore resists homogenisation and the information revolution will empower those seeking to expresses their ways of knowing and protecting nature.