This is the text of a presentation I made at the #Conservation2037 event at the Linnean Society of London in 26 Jan 2017. I hope you enjoy the ideas.

In 1977 Kraftwerk embraced the affordances of emerging technologies to expand the range and repertoire of musical possibilities.

In 1977 Kraftwerk embraced the affordances of emerging technologies to expand the range and repertoire of musical possibilities.

Their innovative electronic music inspired new genres of music: techno, house, hip-hop, dance and so forth.

The Rolling Stones can play Glastonbury. Kraftwerk can play Glastonbury and the Tate Modern.

When the histories of music are written Kraftwerk will be up there as the group who first embraced new technological forces and in so doing shaped both the future of music and the interaction of new technological forces with this major component of human culture.

My message today is that we are at an exciting juncture in the history of conservation. We are at a point in the development of computational technology where – during this decade and the next – new technological forces will shift human society into a different phase.

Conservation – our movement, vocation and profession – has to be part of this phase shift.

We must react and engage with technology in innovative and perhaps radical ways if we are to protect the gains of the past and ensure that conservation remains a cultural force in the 21st century.

In the deeper past c onservationists engaged creatively with new technologies.

onservationists engaged creatively with new technologies.

Orla Johnson pioneered wildlife cinematography: William Beebe nature broadcasting

And then there was Jacques Cousteau – in my view the greatest techno-conservationists of the 20th century.

Such people made nature and nature conservation part of aspirational 20th century culture.

However in the 1970s the shock of ‘environmentalism’ propelled conservation into quite a different relationship with technology.

The environmentalist cause was taken-up by a young, well-educated, middle-class generation with an activist confidence instilled by the 1960s.

The environmentalist cause was taken-up by a young, well-educated, middle-class generation with an activist confidence instilled by the 1960s.

Politicians responded quickly, and were able to do so because the Conservation Foundation had already prepared the policies and people needed to create an international conservation regime.

However, a regime able to exert influence across multiple scales and geographies required three things:

.expertise: systematic information : data management

Fortunately the PC appeared in the early 1980s which empowered conservation in these three key areas.

But this interaction between the political opportunity for conservation, the need for knowledge that was ‘policy fit’, and increasing access to computation and communication exerted a strong centralising force on conservation. For instance

- Technology was still expensive: dbase IV was about £550 (£1400) per licence,

- people with the combined ecological, systematics and computation skills were in short supply,

- international communications was costly and limited,

- access to policy and funders needed strong insider relationships.

Technology and centralisation also provided the finance and know how to transform conservation NGOs into inter-governmental players: it enabled membership management & recruitment, funder databases, and the dot.com boom of the 1990s produced board members with exceptional ambition, strategic acumen and wealth.

The Bingos were borne.

During 1990s technology empowered centralized conservation achieved huge gains, which we should respect and celebrate.

Photo: Susanne Schmitt

Species were saved from the brink of extinction and a huge expansion of protected areas was achieved.

But the centralising forces of the later part of the 20th century also brought downsides and I would argue that our conservation institutions are showing their age.

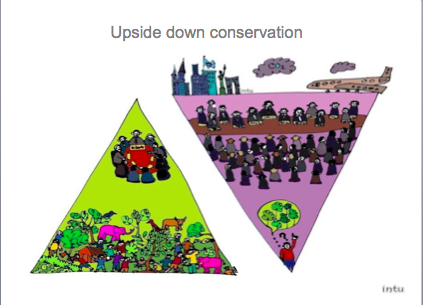

They turned conservation upside down. When I started out most of conservation professionals worked on the ground and very few worked in the central offices.

Thanks to Jeff Sayer and Intu for sharing this image

We had embodied knowledge of nature and worked with local networks to achieve change. We didn’t necessarily earn much but work life was generally purposeful, varied, and rich.

The workscape of conservation you are entering is better illustrated by the triangle in the left. Conservation work has become ever more desk-based and bureaucratic.

We have come to know the nature we conserve in terms of graphs, spreadsheets and maps. We write and adopt blueprints and strategies.

A network of grounded conservationists has been replaced by an army of conservation policy technocrats, managers, marketers and support staff. Professional wages are in decline and career futures narrowing.

In addition, the amazing gains of the past have brought with them huge liabilities which you guys are going to need to address. For example, mega-diverse countries that expanded PA networks post CBD are moving into upper-middle income and this means they have ower eligibility for ODA under common but differentiated responsibility principle. But another was 20th century conservation didn’t have a long term financial plan.

Now for the good news – new technological forces are dissipating the need for a centralisation conservation led by small group of Bingos and opening the possibility of new networks of situated conservationists.

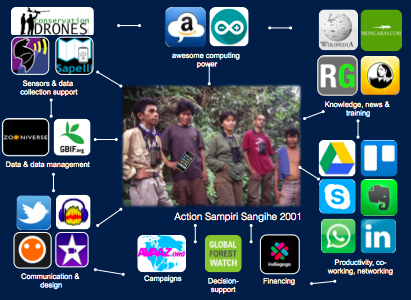

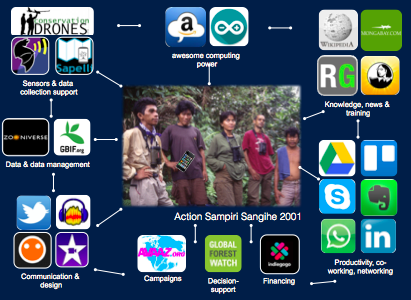

This is Action Sampiri – a hugely effective conservation team that emerged on Sangihe 15 years ago. They split up after 3-4 years because they couldn’t sustain themselves without a bigger conservation patron

All this has changed: Nowadays anyone with a decent laptop and within reach of a broadband has similar access to:

- Knowledge, news and training resources

- Computing power

- Sensors and sensor software

- Data and data management

- Productivity tools, co-working and networking

- Communication and design resources

- Campaigning, decision support and fund-raising support

Today grounded conservation can have similar access to know-how, data, and networks as do those of us working in Universities, government agencies or NGOs. Further the quality and power of these resources is light years beyond anything we could have imagined in 2007.

And all for less than £400 per year!

Humanity is building the greatest machine ever, in the assessment of Kevin Kelly it is the most complex, decentralised, intelligent, collective, accessible, resilient and powerful machine every created. We are entering a future of sapiens plus machine smartness. I future where conservation action can by augmented by hundreds of AIs.

This machine – the cloud – opens the opportunity for a horizontal, networked, technologically empowered conservation movement.

One that transcends nations, sectors, ideology, and scale

It opens the prospect of a future where myriad conservation groups work in myriad localities across our plant. Not as individual efforts but as part of a loose ecosystem of conservation action with transformative power.

But does this mean big conservation is dead?

My view is no. Any effective force needs a degree of central leadership and coordination.

However, if conservation is to be a cultural force in the 2Ist century, if it is to build on the conservation gains of the past and kick on, we must engage with and steer the technological forces that are shaping the future of humanity.

My view is that centralised conservation needs to embrace the culture of the crowd and switch its focus from one of advocate and implementer to one of facilitator and service provider.

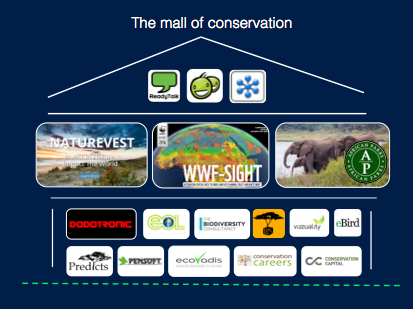

My vision for Conservation 2037 is a future where centralised organisations create platforms, tools and services that empower a new generation of situation conservationist to act, share and suceed.

I imagine the practical expression of Technology Empowered Conservation as virtual mall – places on the web where situated conservationists can visit, shop for tools, kit and services, meet friends, learn and mobilise.

Entering this mal of conservation you might visit

The plush second floor where branded conservation enterprises showcase and sell their triple A conservation products

Then drop down to the first floor where a raft of smaller outlets offer just about everything you could need to assemble an effective conservation action.

After this you might head up to the third floor to hang out with friends, attend networking events or a seminar.

In the central auditorium the mall’s owners will periodically put on exhibitions, TED style talks and other inspirational material.

As you navigate through this virtual mall avatars of our conservation heroes will walk towards you. You may wish to stop them and hear or read about their life, contributions and values.

Situated conservationists will need to own little – everything will be available on subscription or to rent.

They will not be dependent on established organisations for work and the ability to make a change. Should they wish they can create or join start-ups – bands of conservationists – in places where they feel an affinity.

Kelly argues that “Technology is humanities accelerant”

It needs to become conservations accelerant.

It is yours – the cloud belongs to us all..

Let me know what you think